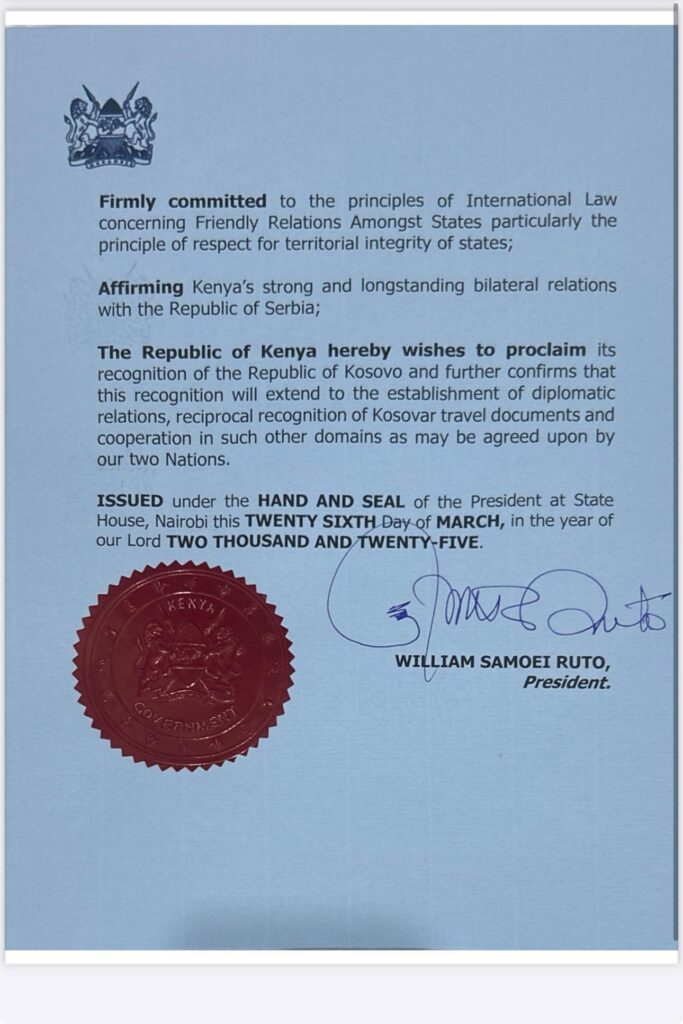

In a move that has stirred both celebration and controversy, Kenya has officially recognized Kosovo as a sovereign and independent nation—becoming the 118th country globally to do so. The announcement, formalized in Nairobi through a diplomatic document signed by President William Ruto and celebrated by Kosovo President Vjosa Osmani, was heralded as a “historic milestone” for Kosovo’s global legitimacy.

But as the two nations raised their flags side by side in Nairobi, deeper questions emerged about what this recognition truly means—for Kenya, for Africa, and for the global diplomatic order.

The recognition was reportedly facilitated by former Kosovo Foreign Minister Behgjet Pacolli, who has long lobbied African nations to back Kosovo’s bid for sovereignty, often in defiance of pressure from Serbia and its allies, including Russia and China. Kenya’s decision, coming after years of hesitation, marks a significant shift in position. Yet, few details have been offered as to why this change occurred now—and what strategic calculations may have influenced it.

From Kosovo’s perspective, this is a diplomatic breakthrough. But from an Afrocentric lens, it also raises critical concerns: What prompted Kenya’s shift? Was it a bilateral gesture of goodwill, a geopolitical maneuver, or part of a broader realignment in Kenya’s foreign policy?

While there is no public evidence that Kenya’s decision was coordinated with the African Union, the absence of an AU position or continental consensus on Kosovo raises questions about whether this recognition reflects Kenya’s own strategic interests—or undermines Africa’s efforts to speak with one voice on global sovereignty issues.

Several African nations—among them South Africa, Algeria, Nigeria, and Ghana—have long resisted recognizing Kosovo, wary of legitimizing secessionist movements that could destabilize their own regions. The African Union itself has maintained a cautious silence, opting not to take a formal stance. Kenya’s unilateral move, therefore, signals a break from this informal but widely respected position of non-recognition.

The symbolic weight of this recognition must not be underestimated. Kosovo, which declared independence from Serbia in 2008, has become a geopolitical fault line between the Western bloc and countries like Russia and China. Western nations, particularly the U.S. and EU member states, have lobbied heavily to secure recognitions for Kosovo, while Serbia has waged an aggressive counter-campaign to reverse them, especially targeting nations in the Global South—including Africa.

Kenya’s new alignment invites speculation. Is this a move to curry favor with Western partners in a moment of economic pressure and diplomatic recalibration? Is Kenya signaling a desire to strengthen ties with the U.S. and EU by supporting one of their foreign policy priorities? If so, does that mark a shift away from Africa-first diplomacy and toward a more transactional global posture?

More importantly, does this recognition set a precedent that could backfire within Africa itself?

Many African countries face ongoing internal movements for autonomy or outright independence. Western Sahara, Somaliland, the Ambazonia movement in Cameroon, and Biafran calls for self-rule in Nigeria all exist in politically tense spaces. By recognizing Kosovo, is Kenya—intentionally or not—endorsing the idea that unilateral secession deserves international recognition?

This is not simply about Kosovo. It is about the power to define sovereignty, the global double standards in how that sovereignty is acknowledged, and whether African nations are asserting or forfeiting their own diplomatic agency.

President Osmani, in her statement, called Kenya’s recognition an “act of courage.” But courage, in foreign policy, is often measured by what one risks and what one protects. Has Kenya strengthened its position—or sacrificed African coherence on international law and territorial integrity?

In an increasingly fractured global order, where new alliances and geopolitical pressures are redrawing international loyalties, African states are repositioning. But for what purpose? Are these realignments about asserting Africa’s independent voice, or do they reveal how easily African sovereignty can still be influenced from outside?

As Kenya opens a new chapter in its diplomatic relations with Kosovo, the continent must ask: Is this a step forward for African global strategy—or a fissure in its foundational unity?